Research into the life and times of a worm that lives in soil and rotting vegetation has won three scientists a share of ten million Swedish Kroner (about £690,000) in this year’s Nobel Prize for Medicine. Sydney Brenner worked in Cambridge during the 1960s and did the groundwork for modern biological science. He recognised that a lowly worm could help us understand how cells live and die. His work on the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has provided researchers with a living model of how cells in organisms mature, differentiate, operate and die.

The body of the nematode worm and our own bodies consist of many different cell types, all originating from a single fertilized egg, which rapidly divides during embryonic development. As the embryo grows its cells mature and begin to specialize, or differentiate, into their different functional forms building up the different tissues and organs in nematode and human alike.

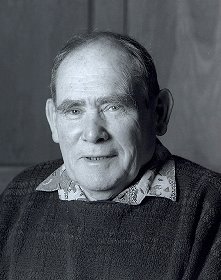

Sydney Brenner

Working in parallel with these growing processes is a third process known as programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Cell death culls unwanted or damaged cells, hollowing out balls of cells to make chambers and vessels, and separating out once-webbed fingers and toes.

Brenner’s masterstroke was to link the analysis of the nematode’s genes with the essential life processes of cell division, differentiation and organ development. John Sulston of The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, extended this research by mapping every cell division and differentiation in the nematode to every tissue. He showed that specific cells undergo apoptosis. He went on to identify the first genetic mutation inherent in apoptosis.

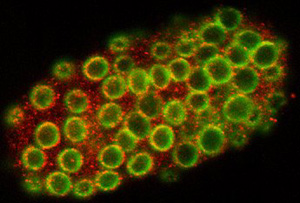

The Horvitz worm – a C. elegans embryo in which all cells have been caused to initiate programmed cell death (apoptosis). (Image: Brad Hersh and H. Robert Horvitz)

Robert Horvitz of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, also built on Brenner and Sulston’s work finding several key genes involved in apoptosis. He figured out how they interact and identified their human counterparts. All three men paved the way for a better understanding of cell processes, which ultimately improve medicine’s approach to diseases such as cancer.

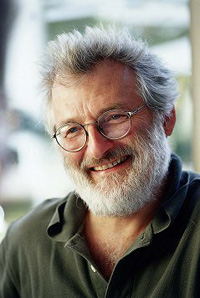

John Sulston

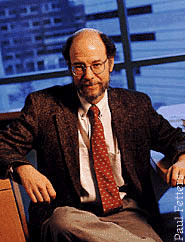

Robert Horvitz

Further reading

Sydney Brenner

http://www.salk.edu/faculty/faculty_details.php?id=7

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/Achievements-and-Impact/Initiatives/UK-biomedical-science/Genome-Campus-and-Sanger-Institute/WTD003479.htm

Robert Horvitz

http://www.hhmi.org/research/investigators/horvitz.html

Suggested searches

Nobel prizes

All material in this article is © David Bradley Science Writer and Intute and may not be reproduced without express permission.