Beneath the beautiful Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming lies a slumbering giant, a supervolcano who wakes every few hundred thousand years and wreaks havoc across hundreds of kilometres as it unleashes millions of tonnes of matter from deep within the earth and pumps ash and debris into the atmosphere potentially creating the natural equivalent of a nuclear winter.

Researchers at the University of Utah, in Salt Lake City, which is well within direct range of Yellowstone have been surveying ground movements at the Park over a seventeen year period. They hope their results will improve our understanding of the geology of this region and so predict more accurately a potential eruption. Earlier research would suggest that Yellowstone last erupted 600,000 years ago and so is long overdue a big blow out.

Christine Puskas surveys Yellowstone for signs of activity using GPS

Doctoral student Christine Puskas working with Professor of Geophysics Robert Smith and colleagues Wu-Lung Chang and former Utah researcher Chuck Meertens used a sophisticated portable Global Positioning System (GPS) antenna to make detailed observations of the rumblings and movements in and around Yellowstone Lake in Wyoming. The team has discovered that the latent power of this huge volcanic hotspot is far greater than previously thought even during the volcano’s half a million year naps. The team analysed measurements from 1987 to 2004 and found that as the earth above the caldera bulges upward, the hotspot itself expends ten times more energy by gradually deforming the Earth’s crust than it would if it were to trigger an earthquake.

They also discovered why ground along the Teton fault, which runs ten kilometres to the south of Yellowstone, moves in a direction opposite to what you would expect. Understanding this perplexing phenomenon could help save lives at nearby ski resort Jackson Hole, should a big earthquake be imminent.

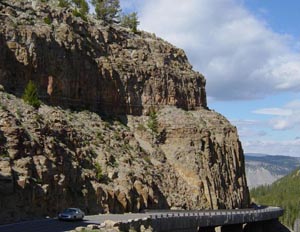

Welded tuff at Golden Gate in Yellowstone was formed by the last supervolcanic eruption

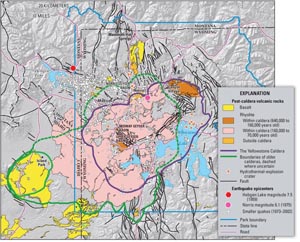

The team also found that molten rock and hot water generated by the hotspot continue to influence the behaviour of the supervolcano’s caldera, the giant crater formed when the weight of the last eruption collapsed on itself 642,000 years ago. That eruption was 1000 times bigger than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington State. The caldera apparently undulates up and down without producing eruptions. Measurements since the newly published study ended in 2004 show the caldera to be rising at a higher rate than ever before observed.

The National Park straddles three overlapping calderas, the crater-like remnants of previous supervolcanic collapses.

The Yellowstone hotspot has had a much bigger effect over a larger area with more energy than ever expected, explains Smith. We’re seeing large-scale deformation of the Earth’s crust in the western United States because of the effects of the Yellowstone hotspot, adds Puskas.

So, is Yellowstone likely to erupt in the near future? The last eruption was more than half a million years ago, prior to that 1.3 million and 2 million years ago. There have been 30 much smaller but nevertheless large eruptions between those periods. The [current] rate [of rising] is unprecedented, at least in terms of what scientists have been able to observe in Yellowstone, Smith adds, We think it’s a combination of magma [molten rock] being intruded under the caldera and hot water released from the magma being pressurized because it’s trapped. I don’t believe this is evidence for an impending volcanic eruption. But it would be prudent to keep monitoring the volcano.

Further reading

Journal of Geophysical Research 2007, 112, B03401

http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004325

Supervolcanoes

http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/1999/supervolcanoes.shtml

Suggested searches

supervolcanoes

volcanoes