Global warming could quickly disrupt ocean processes and lead to drastic climatological changes around the world, according to the latest study by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. Flavia Nunes and Richard Norris studied events that occurred millions of years ago and spanned millennia, but suggest that their findings provide important clues as to the long-term impact of warming on ocean currents and so global climate.

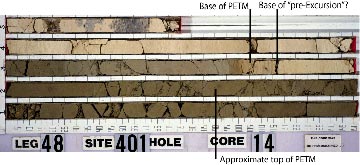

Nunes and Norris investigated the chemical makeup of tiny ancient sea creatures, Nuttalides truempyi, from sediment cores from fourteen locations around the world. Chemical analysis allowed the team to reconstruct changes in deep-ocean circulation through the PETM period. Nutrient levels tell the researchers how long a sample has been near or isolated from the sea surface, thus giving them a way to track the age and flow path of deep sea water. They probed a four- to seven-degree warming period that occurred some 55 million years ago during the closing stages of the Paleocene and the beginning of the Eocene eras. Their data reveal a monumental reversal in the circulation of deep-ocean patterns around the globe, which was triggered by global warming at this time.

Flavia Nunes

The Earth is a system that can change very rapidly, explains Nunes. Fifty-five million years ago, when the Earth was in a period of global warmth – the so-called Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), ocean currents rapidly changed direction and this change did not reverse to original conditions for about 20,000 years. The changes occurred in less than 5,000 years and possibly much quicker given this is the lower error limit on the data. This suggests that the changes that we make to the earth today (such as anthropogenically induced global warming) could lead to dramatic changes to our planet. Indeed, the PETM set in motion a host of important changes around the globe, including a mass extinction of deep-sea bottom-dwelling marine life as well as key migrations of land mammals as migratory routes opened up in the warmer climate.

It’s really interesting how a tiny little shell from a sea creature living millions of years ago can tell us so much about past ocean conditions, said Nunes. We can tell approximately what the temperature was at the bottom of the ocean. We also have an approximate measure of the nutrient content of the water the creature lived in. And, when we have information from several locations, we can tell the direction of ocean currents.

Richard Norris

Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels due to burning of fossil fuels could soon approach the same levels estimated for the PETM period, hinting at profound climatological and oceanic effects.

Ancient sea creatures hint at oceanic effects

Fossil fuels are inextricably entangled with climate change (Credit: David Bradley)

![]()

Ancient ocean currents serve as a beacon on climate change (Credit: David Bradley)

Further reading

Nature, 2006, 439 60-63

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04386

Richard Norris

http://sio.ucsd.edu/Profile/index.php?who=rnorris

Suggested searches

ocean circulation

climate change