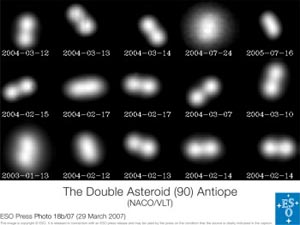

It’s not the most romantic image of heavenly bodies, but the latest observations of a pair of asteroids suggest that the pair is essentially two piles of rubble dancing an eternal pas de deux. The description emerges from a collation of observations from the world’s largest telescopes as well as the small instrument of a backyard amateur. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Paris Observatory have determined that asteroid 90 Antiope consists of two ovoid rubble piles locked in orbit around each other, like two linked dancers sailing around a ballroom. This new perspective, revises the conventional view of Antiope as just another main-belt asteroid; one of millions in orbit in the gulf between Mars and Jupiter. In 2000, the asteroid was resolved into two in a sharp image from the 10-meter Keck II telescope in Hawaii. At the time, however, image quality was not good enough to discern any details of the shapes of the pair, they simply showed up as two bright blobs revolving around their centre of mass.

Berkeley astronomer Franck Marchis and colleagues in France then put the European Southern Observatory’s 8-metre Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile and the University of California’s W. M. Keck II to good use to determine the orbits of the two objects. They found that each rubble pile is about 86 kilometres in diameter and they are separated by about 171 kilometres. The uncertainty was in the size of the components, Marchis told Spotlight, We knew they were less than 100 km in diameter. Using lightcurve observations we could estimate their average size but also their shape.

Antiope (Copyright European Southern Observatory)

There were still numerous uncertainties in those 2003 measurements but in 2005 the team invited fellow astronomers, both professional and amateur to turn their telescopes on the asteroid pair during the predicted mutual eclipse, when one would be hidden behind the other as observed from earth. This occultation would cause a significant drop in brightness on 31st May 2005. At the point of totality, team member Tadeusz Michalowski at Adam Michiewicz University’s Astronomical Observatory in Poznan, Poland, e-mailed Marchis and colleagues from South Africa to confirm the eclipse and recorded the dip in Antiope’s brightness from the South African Astronomical Observatory.

Over the next six months, at Marchis’ invitation, amateurs and professionals from as far afield as Brazil, France, Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean and Grass Valley, California, observed repeated occultations, as well as shadows passing over one of the pair. Amateur astronomer Peter Dunckel, 75, a retired paper company executive who observes from the backyard of his vacation home in Grass Valley observed the binary pair for 35 hours over a period of six weeks, recording Antiope’s brightness every minute with a CCD camera attached to his Maksutov Newtonian reflector telescope.

Asteroid eclipse (NACO/VLT)

This is the first publication I’ve had in a professional journal, Dunckel says, and I’m really happy about it. He adds that, What is really a thrill is to have my little 7-inch telescope alongside an 8-metre telescope on the same paper; it is unbelievable. It is the large number of frequent observations that amateurs can make that can offset the size of the telescopes, Marchis explains. You can time the orbits more precisely when a mutual event happens, which allows you to extract also the size, shape and surface detail of each component, and also what it’s made of.

Franck Marchis

Antiope is itself the remnant of an ancient asteroid, dubbed Themis, which astronomers estimate was destroyed around 2.5 million years ago, probably by a collision with another asteroid. Despite this intensive study, the origin of this unique doublet still remains a mystery, adds Pascal Descamps of Paris Observatory. The formation of such a large double system is an improbable event and represents a formidable challenge to theory.

Further reading

Icarus, 2007, 187, 482-499;

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2006.10.030

Franck Marchis’ webpage

http://astro.berkeley.edu/~fmarchis/

Suggested searches

asteroids