Chemists working on tight budgets in developing countries may be able to swap flasks of laboratory reagents for extracts of celery and potatoes, or cassava and carrots and other inexpensive, locally available vegetable products and food waste. The idea could open up research in developing countries where the high price of some reagents can preclude all but the most basic of chemistry.

Writing in the March 23 issue of the Journal of Natural Products, Geoffrey Cordell of the University of Illinois at Chicago and colleagues in Brazil explain that the high cost of imported reagents is a serious problem for academic researchers and even chemical and pharmaceutical laboratories in developing countries. They explain how some of the more than 7000 vegetable crops grown throughout the world might provide substitute reagents for laboratory work.

Geoffrey A. Cordell

Plants are veritable chemical factories in their own right. Metabolic processes in the hundreds of thousands of different species of plant carry out complex transformations that even the best synthetic organic chemist will struggle to emulate in many instances. Plants easily combine general compounds such as acetates, isoprene precursors, amino acids, and other small molecules through various enzyme-controlled biochemical reactions into a vast array of more complicated molecular structures. Enzymes that have had millions of years to evolve are highly efficient and specific, using just enough raw material to make the end product. Such skills are beyond the reach of even the most up to date laboratories without having to rely on wasteful reaction schemes and separation procedures to remove by-products.

The diversity of plant natural products is vast and chemists find new structures on an almost daily basis. A staggering 140,000 secondary metabolites are known in structural detail all of which fall into one of almost 6000 different basic chemical structures. Any one of these might be used as a starting material for making a novel pharmaceutical or agrichemical, or other material.

Cassava for the developing chemist (Copyright © 2005 David Monniaux, reproduced under GNU licence)

Cassava for the developing chemist (Copyright © 2005 David Monniaux, reproduced under GNU licence)

The evaluation of locally available vegetables, fruits, common plants, and natural waste products for a selection of standard organic chemical reactions of commercial significance could prove to be a very valuable economic endeavour, says Cordell, It may well offer new opportunities to expand the role of natural products as sustainable chemical reagents where high-cost, non-renewable reagents are presently used.

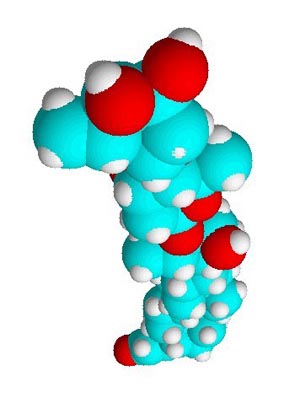

Digitoxin, a natural plant product, can be converted into new compounds (Structure by David Bradley)

Cordell and his colleagues at the Federal University of Ceara point out that there are approximately 7000 vegetable crops used in food and agriculture throughout the world. In their work, they have highlighted one crop species alone, cassava, or manihot, that can carry out highly specific reduction reactions to convert raw starting materials into more complex and potentially useful products.

“The potential use is one area that needs to be explored,” Cordell told Spotlight, “Given the available waste from manihot, for example, it could possibly be scaled up to the small-scale drug synthesis level and provide a reusable (5-6 times over) catalyst. We are looking at reproducibility and temperature factors now.” He adds that his team’s work will hopefully inspire others. “My wish is to get other groups around the world to look at their local veggies for potential reactions and to broaden the scope of the reactions,” he told us.

Numerous plants are already used for industrial applications, such as flavourings, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and even in the construction industry, and other uses. The wider use of waste products from crop cultivation could soon be a growth area for chemistry.

Further reading

J. Nat. Prod., 2007, in press

http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/np0680634

Geoffrey A. Cordell

http://foto.pharm.uic.edu/mcp/people/cordell_ga.html

Suggested searches

organic chemistry

chemical reactions