A vast cloud of methyl alcohol, spanning some 463 billion kilometres and wrapped around a stellar nursery could help astronomers explain the formation of some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Lisa Harvey-Smith revealed details of the observations at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting on 4th April.

Harvey-Smith and Jim Cohen of Jodrell Bank Observatory analysed measurements from the recently upgraded MERLIN radio telescopes, studying a region in our galaxy called W3(OH). Stars are continually being formed in this region as gravity pulls gas and dust together.

Lisa Harvey-Smith

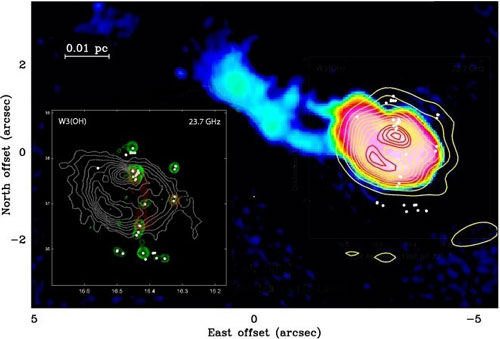

Their analysis revealed the existence of giant filaments of gas that are emitting microwave radiation; they act as masers. The filaments of gas form giant bridges between known microwave hot-spots in W3(OH). The largest filament is 463 billion kilometres long and appears to be rotating as a disc around a central star. This rotation resembles the planetary accretion discs seen as planets form around young stars, but on a stellar scale. Harvey-Smith explains that these filaments occur at the shock boundaries where large clouds of gas collide.

Our discovery is very interesting because it challenges some long-accepted views held in astronomical maser research, Harvey-Smith says. Until we found these filaments, we thought of these masers as point-like objects or very small bright hotspots surrounded by halos of fainter emission.

Digitized Sky Survey (Credit: ESA/ESO/NASA FITS Liberator)

The technical upgrades to the UK’s MERLIN telescope network have allowed astronomers to obtain much clearer images of such masers and so get a complete picture of all the radiation surrounding them. In the new study, the Jodrell Bank team looked at the motion of the W3(OH) star-forming region in three-dimensions and also measured physical properties of the gas such as temperature, pressure and the strength and direction of the magnetic fields. This information is vital when testing theories about how stars emerge from primordial gas in stellar nurseries.

White circles are methyl alcohol maser spots superimposed on the star forming region. The left panel shows the extended methanol (green) and hydroxyl (red) masers plotted over the same region.

There are still many unanswered questions about the birth of massive stars because the formation centres are shrouded in dust, Harvey Smith says. The only radiation that can escape is at radio wavelengths and the upgraded MERLIN network is now giving us the first opportunity to look deep into these star-forming regions and see what’s really going on.

Harvey-Smith joked that Although it is exciting to discover a cloud of alcohol almost 300 billion miles across, unfortunately methanol, unlike its chemical cousin ethanol, is not suitable for human consumption!

Harvey-Smith has now left Jodrell and is working at the Joint Institute for the Very Long Baseline Interferometry in Europe.

Further reading

Lisa Harvey-Smith

http://www.physics.usyd.edu.au/~lhs/

Suggested searches

star formation

star birth