Researchers from the University of Montpellier II, France, the Institute of Geology of China, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, France) have used an incredibly intense beam of X-rays to peer back into deep time at a group of enigmatic fossils from the Devonian (about 400 million years) period. The X-rays allowed the scientists to see through the mists of time to reveal that the tiny fossils are the fructification organs of so-called charophyte algae.

Charophytes are land plants that live in fresh water even today, but the evolutionary origins of these plants and indeed the identity of their oldest fossils has until now remained hazy. Charophytes are a well known group, explains ESRF’s Paul Tafforeau. Only the very old fossils are really problematic because they can be very different from the more modern forms. These fossil charophytes belong to an enigmatic group known as the Sycidiales, which were discovered in 1934, and variously thought to be bracken seeds, corals, and even the eggs of crustaceans. Now, Monique Feist and colleagues, Junying Liu and ESRF’s Paul Tafforeau, have made a breakthrough in understanding these ancient plants, which could provide environmental scientists with important new clues about past climate change.

Paul Tafforeau

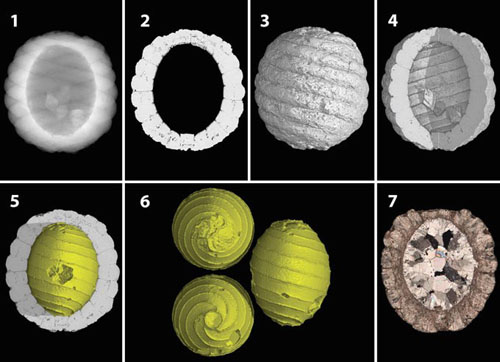

The X-ray synchrotron microtomography used in this study revealed in three dimensions microscopic internal detail without damaging the fossils; all other techniques would involve their destruction.

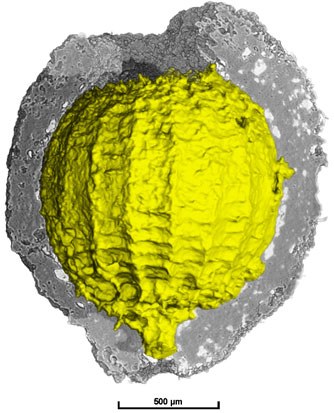

Among the surprising revelations was the presence of a calcified utricule embedding these fossil fructifications. An utricule is a protective layer that is thought to prevent the plant’s reproductive cells, zygotes, from drying out in temporarily arid environments, and was previously only seen in charophytes from the much more recent Mesozoic, secondary era. As no modern charophyte presents an utricule, the function of this structure is only a hypothesis, Tafforeau told Spotlight. We have strong arguments to link it to an adaptation against desiccation, but as often in paleontology, it is impossible to have a real certitude.

Monique Feist

The presence of an utricule in these fossils suggests that these old charophyte algae were adapted to a harsh environment, maybe of very dry summers and little water. As the utricule is extremely developed among some Sycidiales (in particular the Chinese forms), adds Tafforeau. Then, it is probable that the water environments were dried during a quite long time probably each year. If this were the case, then the parent plant probably died during the dry season, and a new generation developed the following year from the fructifications that were resistant to desiccation when the waters return. Tafforeau says that this indicates a very strong seasonality with dry and wet seasons. Nevertheless, very different kinds of highly seasonal climates can be found nowadays, he adds, hence it is difficult to infer precisely the climate of 400 millions years ago from a single characteristic of fossil algae. It provides some data, but other information will have to be determined to perform an accurate paleoclimatic reconstitution.

Charophytes (Credit: Paul Tafforeau – ESRF)

Charophyte utricule (Credit: Paul Tafforeau – ESRF)

Further reading

Am J Botany, 2005, 92, 1152-1160

http://www.amjbot.org/cgi/content/abstract/92/7/1152

European Synchrotron Radiation Facility

http://www.esrf.eu/

Suggested searches

fossils

X-rays