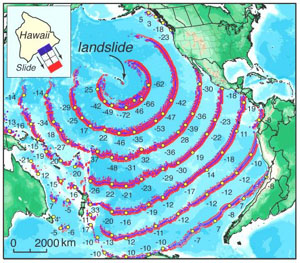

Children playing on the beach are all too familiar with land slip and the devastating effects it and the waves it can produce on their shorelines sandcastles. But, when an oceanic volcano, such as Kilauea on Hawaii, undergoes a ‘flank collapse’, when the side of the volcano slips off into the ocean the resulting giant wave train created by the traumatic displacement of a great volume of water can have a savage impact on distant shores as a tsunami slams into a coastline.

Flank collapses involve great masses of rock – up to 5000 cubic kilometres by one estimate – and at their worst could make catastrophic and life-threatening tsunami, among the islands or even across thousands of nautical miles. Tsunami have long wave periods and so reach far inland once they hit a coast. Kilauea is constantly monitored for any rocky disturbances so that early warning of an outgoing tsunami can be made; the team also monitors for earthquakes and volcanic activity. Now, Peter Cervelli of Stanford University in California and his team believe they have unearthed a phenomenon that may be involved with flank collapse.

Cervelli in traditional Hawaiian garb setting up a GPS monitor

The researchers observed over a period of three days in November 2000 a slipping of the flank of Kilauea by some 9 centimetres. Interestingly, this was at a time when there was no seismic rumbling (geologists’ standard signal of rock movement). They report in Nature that this movement was preceded by unusually heavy rainfall, and they speculate that it may have been the heavy rains that triggered the movement as the region’s water table changed.

This 9 cm slip is very small compared with a full-blown flank collapse of the size needed to produce a tsunami but the Stanford team reckon their findings suggest that geoscientists need to monitor risky volcanoes with Global Positioning System (GPS) instruments that can spot movements even when there is no conventional seismic activity.

Simulated tsunami waves following a volcanic flank collapse

Steven Ward of the University of California in Santa Cruz points out that the geological record tells us that mountain ranges have been built and then washed down to the sea; that entire ocean basins have opened and closed like a door, so it should be of no surprise that on the geological timescale volcanic islands are but dust on the wind. He adds, in the same issue of the journal, that oceanic volcanoes usually grow too steep to support their entire mass and slough off flank material.

GPS in position

Sonar has revealed this to be true for most volcanic island chains. The Hawaiian Islands have seen seventy flank collapses in the past 20 million years. The last one was just a few hundred thousand years ago, although there seems to be one flank collapse somewhere on the globe approximately every 10,000 years.

The small slippage observed by Cervelli and his team suggests that Kilauea may in for a bigger shock in the near future. The near future to an earth scientist though might be another few millennia or even millions of years. But, as children soon learn shoreline sandcastles are fragile at the best of times. Kilauea could be due for a full-blown flank collapse, which with several thousand cubic kilometres of rock involved would be equivalent to Majorca or Rhode Island shifting tens of kilometres sideways.

Ward is convinced that the Cervelli work is not simply due to signal noise. For me, their map of a dozen GPS displacement arrows all pointing out to sea far beyond their error ellipses tells the whole story, he says, What else can they indicate but some early stage of one of those flank collapses that litter the geological record? A 2,000 cubic km piece of Hawaii is slip-sliding away.

Cervelli and his team hope that their ongoing studies will provide early warning for the Hawaiian islanders and for those distant shores that might lie in the path of a tsunami.

Further reading

Nature, 415, 1014 (2002)

Steven Ward

http://es.ucsc.edu/personnel/Ward/index.html

Suggested searches

Flank Collapse

Landslides

Volcanoes

Tsunami