An inexpensive material that produces hydrogen from plant sources with less waste than other processes could be used to run fuel cells, one of the alternative energy sources being developed for vehicles and as back-up power generators for hospitals and other large installations.

Chemical engineer James Dumesic and graduate students John Shabaker and George Huber, of the University of Wisconsin at Madison, have developed a hydrogen-producing catalyst that uses less expensive materials and produces lower levels of contaminants than current processes, while extracting the element from common renewable plant sources.

Dumesic, among the crop (Credit: James Beal, University of Wisconsin)

Dumesic and his colleagues have developed the catalyst from nickel, tin and aluminium and have used it to speed up the so- called aqueous-phase reforming (APR) reaction, a simple process which can be used to convert biomass – plant by-products, such as carbohydrates and sugars – into hydrogen. The catalyst works as well as those based on precious metals such as the rare noble metal platinum, which is £10 per gram. The APR process can be used on the small scale to produce fuel for portable devices, such as cars, batteries, and military equipment, says Dumesic, But it could also be scaled up as a hydrogen source for industrial applications, such as the production of fertilizers or the removal of sulphur from petroleum products.

The Wisconsin team is now working with Virent Energy Systems in Wisconsin as part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grant to develop catalysts for generating fuels from biomass.

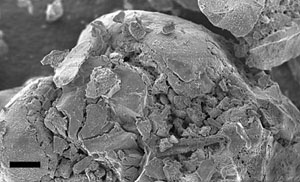

Scanning electron micrograph of the Raney-NiSn catalyst after reduction at 260 degrees Celsius in H2 (hydrogen gas) and subsequent passivation (slow exposure to air, so the catalyst does not rapidly oxidize) (scale bar is 10 microns).

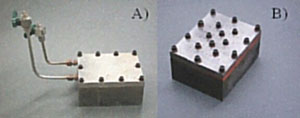

Dumesic and his colleagues tested over 300 combinations of catalytic metals using a microscale reactor that can test almost 50 catalysts simultaneously until they found just one that could compete with platinum in the APR process. Intriguingly, the best catalyst turned out to be a modified version of Raney nickel, an alloy invented by Murray Raney in the 1920s. Raney-nickel is a porous material composed of 90% nickel and 10% aluminium However, the addition of a small amount of tin precludes the formation of methane, a by-product when native Raney nickel is used to treat biomass.

Photos of high-throughput reactor showing A) reactor with common headspace top plate (used for catalyst reduction) and B) reactor with isolated headspace plate (used for reaction and gas chromatograph analysis). (Credit: G. W. Huber, J. W. Shabaker)

According to Dumesic, an alternative to platinum APR catalysts will be essential if the hydrogen economy is to become feasible. We had to find a substitute for platinum in our APR process for production of hydrogen, since platinum is rare and also employed in the anode and cathode materials of hydrogen fuel cells to be used in products such as cars or portable computers, he explains.

Further reading

Science, 2003, 300, 2075-2077

http://www.sciencemag.org/

James Dumesic

http://www.engr.wisc.edu/che/faculty/dumesic_james.html

Virent Energy Systems

http://www.virent.com/

Suggested searches

Catalysis

Fuel cells