The secret ingredient in a future biological computer is to add a little DNA. But, making hybrid devices from a silicon chip and a strand of genetic material means mixing hard-wired microelectronics technology with the softer world of molecular biology.

Now, chemists at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne have come up with a solution that could lead to new lab-on-a-chip devices and biological sensors for use in medicine and environmental analysis. It might even one day allow biology to compute or provide an interface between electronic devices and living things.

Ben Horrocks

Newcastle chemists Benjamin Horrocks and Andrew Houlton and their colleagues have devised a way to automate the solid-phase synthesis of DNA on a semiconductor chip. They believe their method could readily be adapted to the conventional fabrication techniques of photolithography used in the microelectronics industry to pattern the microscopic transistors and circuitry on a computer chip.

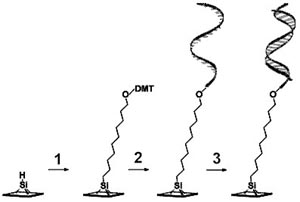

The team recently reported how it has found a way to attach a DNA sequence of just seventeen nucleotides to a silicon surface modified with organic molecules. The key to unlocking hybrid DNA chips lies in the team’s use of bifunctional organic molecules. At one end the molecule has the right chemistry to allow it to be attached to an oxide-free silicon surface. The other end of the molecule has a functional chemical group on which a DNA strand can be grown using an automated DNA synthesizer of the kind found in biotech laboratories the world over.

Andrew Houlton

The team is working with two aims in mind – first, the development of chemical sensors and secondly the synthesis of DNA on silicon surfaces for nanoscale molecular architecture. This addresses the projected reduction in the size of electronic components which by 2015 are predicted to be of the order of nanometres (i.e. built from molecules), explains Houlton.

Gel electrophoresis reveals DNA is attached to the silicon

Previous endeavours in this area have generally used glass in preference to silicon wafers and those that have focused on silicon have applied organic molecules to an oxidised surface rather than the naked silicon chip. The Newcastle team has now confirmed that it is possible to cover the surface of a silicon chip with DNA strands. Moreover, the 17-base DNA strands can be coupled with the complementary DNA strand making the familiar DNA double helix. From the nanodevice perspective the importance of the team’s work lies in their ability to pattern the surface of the silicon rather than simply randomly deposit DNA strands. Patterning using the printing and etching techniques of microelectronics fabrication means they can tightly control the arrangement of the DNA on the surface and so produce what might one day become molecular circuitry.

A DNA-patterned silicon surface

Sequential modification of a silicon surface with DNA

Further reading

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 41, 615 (2002)

http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/90512278/ABSTRACT

DOI: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020215)41:4<615::AID-ANIE615>3.0.CO;2-Y

Benjamin Horrocks

http://www.ncl.ac.uk/chemistry/staff/profile/b.r.horrocks

Andrew Houlton

http://www.ncl.ac.uk/chemistry/staff/profile/andrew.houlton

Suggested searches

Molecular Electronics

Nanotechnology