Cambridge and Caltech astronomers have devised a new digital sensor for their telescopes that effectively cancels out the twinkling caused by the Earth’s atmosphere and allows them to obtain pictures of distant heavenly bodies that are clearer even than those obtained by space telescopes, such as Hubble.

Everyone knows the nursery rhyme, Twinkle, twinkle, little star, none are more frustrated by it than ground-based astronomers hoping to probe the depths of space. Even in the clearest air atop an Andean mountain, the stars still twinkle. Luckily there is now hope for the vertically challenged telescope user in the form of a new high-speed, almost noise-free digital camera developed by a team at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge led by Craig Mackay working with Caltech’s Nick Law and his group.

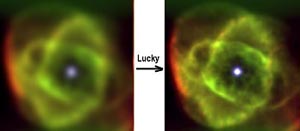

A Lucky break lights up new stars

Previously, astronomers have tried to develop adaptive optics to correct the blurring caused by atmospheric distortion of the light from distant stars entering a telescope. Unfortunately, these devices have only proven themselves in the infrared region of the spectrum where twinkling can be cancelled out effectively. It is the visible region that has left ground-based astronomers envious of the images obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope. Until now.

The new camera works by recording a sequence of images at twenty frames per second or faster. The system software then checks each image, selects the sharpest and least smeared images and then the images are combined to cancel out the random fluctuations using a technique the team calls Lucky Imaging. The technique is similar to that used to cancel random noise in other areas of science such as spectroscopy, where a sequence of spectra for the same sample are recorded, added together and the peaks and troughs of noise cancel each other out.

Clearer view of the Cat’s Eye Nebula with Lucky Camera

The team has tested the method with the 5.1 m telescope at Mount Palomar. With its conventional imaging sensors, the telescope produces images an order of magnitude less detailed than those from Hubble. With the Lucky Camera in place, the team was able to obtain images that are actually twice as sharp as those produced by Hubble, all without leaving the comfort of planet Earth. These are the sharpest images ever taken either from the ground or from space, say the researchers, To get sharper pictures you have to use an even bigger telescope. Indeed, they are now investigating the possibility of getting Lucky with the 8.2 m Very Large Telescope of the European Southern Observatory in Chile and the 10 m Keck telescopes on the top of Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

So far, the team has already discovered many multiple star systems which are too close together and too faint to find with any standard telescope. Stars separated by as short a distance as one light-day have been resolved in images of the globular star cluster M13 which lies at a distance of some 25,000 light-years from earth

Further reading

Dr Craig Mackay homepage

http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~optics/people/cdm.htm

Lucky image homepage

http://www.ast.cam.ac.uk/~optics/Lucky_Web_Site/index.htm

Suggested searches

telescopes

hubble