Just as a forensic scientist can find out what happened at a crime scene so a forensic seismologist can fingerprint the Earth to pinpoint unidentified explosions.

Geoscientist Terry Wallace of the University of Arizona is using data from some 3600 seismic stations – that normally look for volcanic and earthquake activity – to spot sinking submarines, industrial explosions, nuclear weapons testing, landslides, and other unidentified phenomena that make the Earth move.

Terry Wallace (image courtesy of Wallace)

Seismological tools and theory can be used as constraints to tell when an accident occurs or something that’s not accidental, like a nuclear explosion, explains Wallace, We can then put behind that some ideas of how big an explosion might be, or if it’s a landslide, how big the landslide might have been, or how far the rocks have fallen, for example.

He and his colleagues have confirmed, for instance, the when and where of Indian and Pakistani nuclear testing in the late 1990s. They have also studied the claim that Iraq tested a nuclear weapon in 1989. The alleged test was reported to have been carried out beneath Lake Rezazza, approximately 100 km southwest of Baghdad at 10:30h on 19 September. Wallace and his colleagues examined the global earthquake catalogues produced by the International Seismic Center and the US Geological Survey and say they reveal no seismic disturbances at all in Iraq that day. Moreover, they say there has been no seismicity within 50 km of the reported test site for the years 1980 to 1999. One problem with the assertion that no weapons testing took place, they point out, is that the detection threshold for these global catalogues was just magnitude 4.0 in 1989 so a smaller magnitude event may have not been picked up by the sensors. Thankfully, national catalogues for Israel, Jordan and Iran reported no seismic event in the region on that date either (19 September 1989).

Nuclear tests (image courtesy of Wallace)

The lower detection limit of modern seismic testing is only limited by the natural noises of the Earth. However, comparisons between results from different stations will reveal very fine detail. Explosions and earthquakes both generate seismic waves, but they have distinctive frequency signatures much like the tones of a voice, Wallace told Spotlight, Just as most children’s voices can be distinguished from adults, seismograms can be used to identify if a disturbance was caused by an earthquake or an explosion.

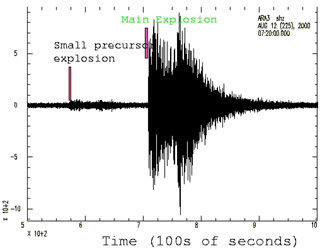

Two explosions (image courtesy of Wallace)

Wallace and his team have also analysed the seismic activity that occurred on the day the Russian submarine Kursk sank north of the Kola Peninsula. There were two explosions on 12th August 2000 associated with reports of this vessel sinking. There was a gap of two minutes between the explosions, the second of which was much bigger. Seismometers detected both up to 4500 km away. Calculations that compare results from different seismometers revealed that the second explosion was the equivalent of five tonnes of TNT exploding, which Wallace suggests was a warhead detonating. Our findings were corroborated when the Russians released their report in July this year, says Wallace.

The Kursk sank on 12th August 2000, in the Barents Sea

Wallace revealed the latest details of his Earthly forensics investigations at the 2002 American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco in December. He revealed that he and his colleagues are investigating the sinking of the USS Scorpion submarine near the mid-Atlantic ridge in 1968, the sinking of another Russian sub in the Baltic in 1989, and the sinking of a large oil derrick in the North Sea that produced a 3.5-magnitude earthquake when it hit the ocean floor.

Water seismometers, or hydrophones, are even more sensitive to water rumblings than are the land-based versions. Using a hydrophone in the water, we can see the explosion of one stick of dynamite anywhere in the world. That’s how quiet the oceans are. So if you are going to hide something, don’t do it in the water, Wallace says.

The whole research effort for my group is to develop as big a portfolio as possible. This way, when we see an industrial accident where a fireworks factory blows up or a gasoline tank blows up, we have all the different kinds of seismic records we can get from that and we have characterized them. Then the next time something like that happens we have some experience to draw from. We’ve got some fingerprints left over to help us understand what is happening, Wallace adds.

Further reading

Suggested searches

Seismology

Seismic waves