A Chinese library is an unlikely place to go looking for catastrophic hurricanes, but a US geography professor reckons that he can unearth ancient storms by trawling the archives of China dating back to the time of the Song Dynasty.

Kam-biu Liu of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge made the news two years ago when his work on core samples from coastal lakes and shorelines revealed that catastrophic hurricanes hit the US Gulf Coast every three centuries or so. Now, he is getting to the core of archaic weather via a different route.

Kam-biu Liu

Liu’s previous work involved carbon-dating coastal core samples to find out when prehistoric storm surges washed sand into the lakes. His detailed studies of cores dating back five millennia have given birth to a new field of science – paleotempestology – the study of past tropical cyclone activities using geological methods.

But, historical records from Guangdong Province on the southeastern coast of China, have now revealed details of some 1,133 typhoons that led to serious loss of life and property in this area. Liu has spotted clusters of very powerful storms happening in a fifty-year cycle in this region. The period studied spans 1,025 years beginning in 975 AD, and, according to Liu is the longest documentary record of tropical cyclone activity ever compiled.

First Song Emperor Taizu

The significance of the discovery that major tropical cyclone activity occurs every fifty years has not been lost on the Chinese government. Guangdong Province is now one of the most rapidly expanding economic regions in China and its long and exposed coastline makes it highly vulnerable to catastrophic storm surges and coastal flooding. Some 158 cyclones blasted Guangdong between 1949 and 1988, with thirty-three of those gusting at wind speeds above 73 mph making them typhoons. If a typhoon the strength of Hurricane Camille were to hit Guangdong Province today, the destruction and possible loss of life would be immense, Liu suggests, The logical question to ask is, what is causing these cycles?

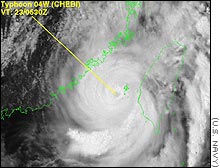

Super Typhoon Winnie (1997) approaching China

The answer could lie in Chinese dynastic histories. In North America the record is very short, Liu explains, Even after Columbus it’s very sketchy for the first hundred years. And the Gulf Coast has virtually nothing before the 17th century. Contrast the American records with the meticulous historical records kept as an official history by each dynasty over the last three millennia. These dynastic histories carry with them details of natural disasters, including typhoons.

1997’s Typhoon Chebi

Studying in Hong Kong and Beijing libraries Liu and his team have worked their way through hundreds of records highlighting entries such as the following from the Zhenhai County Gazette: In the sixth lunar month of the sixth year of the Emperor Chongzhen (1633 AD), a typhoon struck. Torrential rain fell for ten days. Houses collapsed. Naval battleships were drifting in the sea; eight or nine out of ten were destroyed, drowning numerous soldiers. Since the first year of Chongzhen there was no year without typhoon strikes. The damage was especially serious this year. It was widely believed the culprit was a mischievous dragon.

Liu and his team checked the reliability of the historical record by comparing it with a 26-year period, from 1884 to 1909, when the historical record overlapped with instrumental observations. The historical record, it seems, under-reported the number of tropical cyclones. But, the under-reporting is much smaller if only typhoons are counted. Liu points out that the year-by-year accounts in these Chinese records are far more accurate than any sedimentary core research. The sedimentary records are accurate only to between 100 and 200 years. They can reveal the major storm cycles, but the historical record is essentially at a much higher resolution and shows annual activity within these major cycles.

Researchers believe that a colder climate and a lower sea surface temperature are at the root of reduced hurricane activity and intensity. However, a peak in landfall activity occurred between 1660 and 1680, which was the coldest and driest period the Northern Hemisphere had experienced over the last 500 years. Liu conjectures that climatic changes merely shift the path of tropical cyclones further south so that they cause more landfalls in Guangdong Province. But, in order to find out what causes storms to follow their cycles, Liu and his colleagues are working their way through library records along the coast of China, and plan to branch out into the historical records of Japan and the Philippines. Integrating the historical data will help us understand the climatological mechanisms that control these activities, Liu explains. Once we understand those, it will help us predict these storms.

One clue to the storm cycles that can be revealed by a modern scientific approach is that the periods of greatest storm activity and typhoon landfalls occur when there is very little sunspot activity. Indeed, such a period occurred between 1660 and 1680, which was marked by very low sunspot activity. The relationship between sunspot activity and earth’s climate is still very unclear, but revelations in Chinese dynastic history could play a role in finding new answers to the ancient problem of predicting seriously stormy weather.

Further reading

Kam-biu Liu

http://www.ga.lsu.edu/liu.htm

Suggested searches

Paleotempestology

Hurricanes

Climatology